If there’s one thing you don’t want to be in Quebec City, it’s British. We’re not very popular over there and haven’t been since 1759 when we fought the French on the Plains of Abraham and won control of New France, opening up the St Lawrence river and giving British ships access all the way to the Great Lakes.

A lot of the guides giving tours around the various battlefields and museums talked about how well the French and the indigenous First Nation population got on together back when the French were in charge. Then the guide would pause for a moment and look around at the group of tourists, obviously trying to assess everyone’s nationality. Then, they would sigh and say in a censorious tone ‘And then the British …’ and we would try to look very unBritish, as we learnt exactly what the perfidious Brits had done next.

Although I have to say that the French army didn’t do themselves any favours with their preoccupation with personal hygiene.

In the Plains of Abraham Museum there is a long, thin, green bottle on display, with a label explaining that this is an Emperor bottle – a design originally created for Napoleon. French officers were worried about body odour and were in the habit of wearing fragrance to give the impression that they were daisy-fresh all day long. This bottle was niftily designed to be slipped into a boot, so as to be accessible at all times. Any time a général or a capitaine felt a bit sweaty he could stop his horse, reach down into his boot for his eau de cologne and freshen up before resuming battle, confident that he wasn’t offending his enemies’ sense of smell.

Now, I’m no expert in these matters, but I get the impression that their priorities were a little skewed. General Wolfe’s victorious campaign at Quebec involved taking the French by surprise and approaching by sea rather than land. The British army set sail in the middle of the night and landed silently in a small cove where the entire force of over 4,000 men had to disembark and climb a practically sheer cliff, dragging two cannons up the cliff with them. The French were duly surprised when the British popped up on the cliff at daybreak, and the subsequent battle lasted less than thirty minutes. But I can’t help wondering whether the British victory might have been less decisive if our soldiers had been a bit more aware of their personal hygiene after such a sweaty climb in full uniform, and had stopped at the top of the cliff to freshen up a little. This would have given the French a few vital minutes in which to complete their own toilette and get into battle formation.

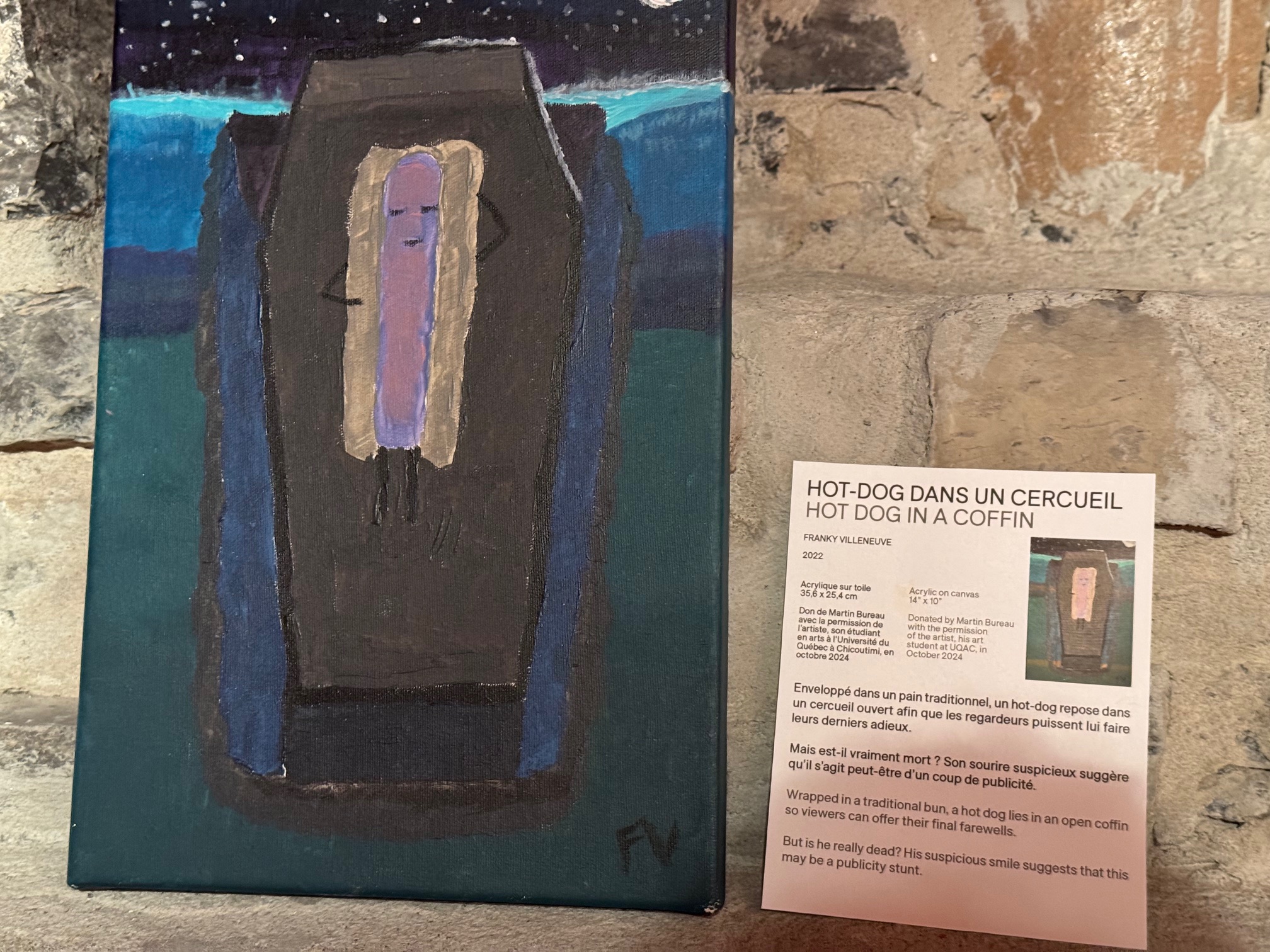

I was pleased to see that, apart from battles, Quebec is a city that doesn’t take itself too seriously, and there was evidence of that in the wonderful gallery called The Museum of Bad Art. It’s a collection that was started by Scott Wilson after he discovered this painting, Lucy in the Field with Flowers:

As the description says, The motion, the sway of her breast, the subtle hues of the sky, the expression on her face; every detail cries out “masterpiece!”

Scott’s friends persuaded him that this oeuvre should be on display somewhere, so he went on to acquire other great works and set up his gallery:

You gaze at them, and the only question that springs to mind is ‘Why?’

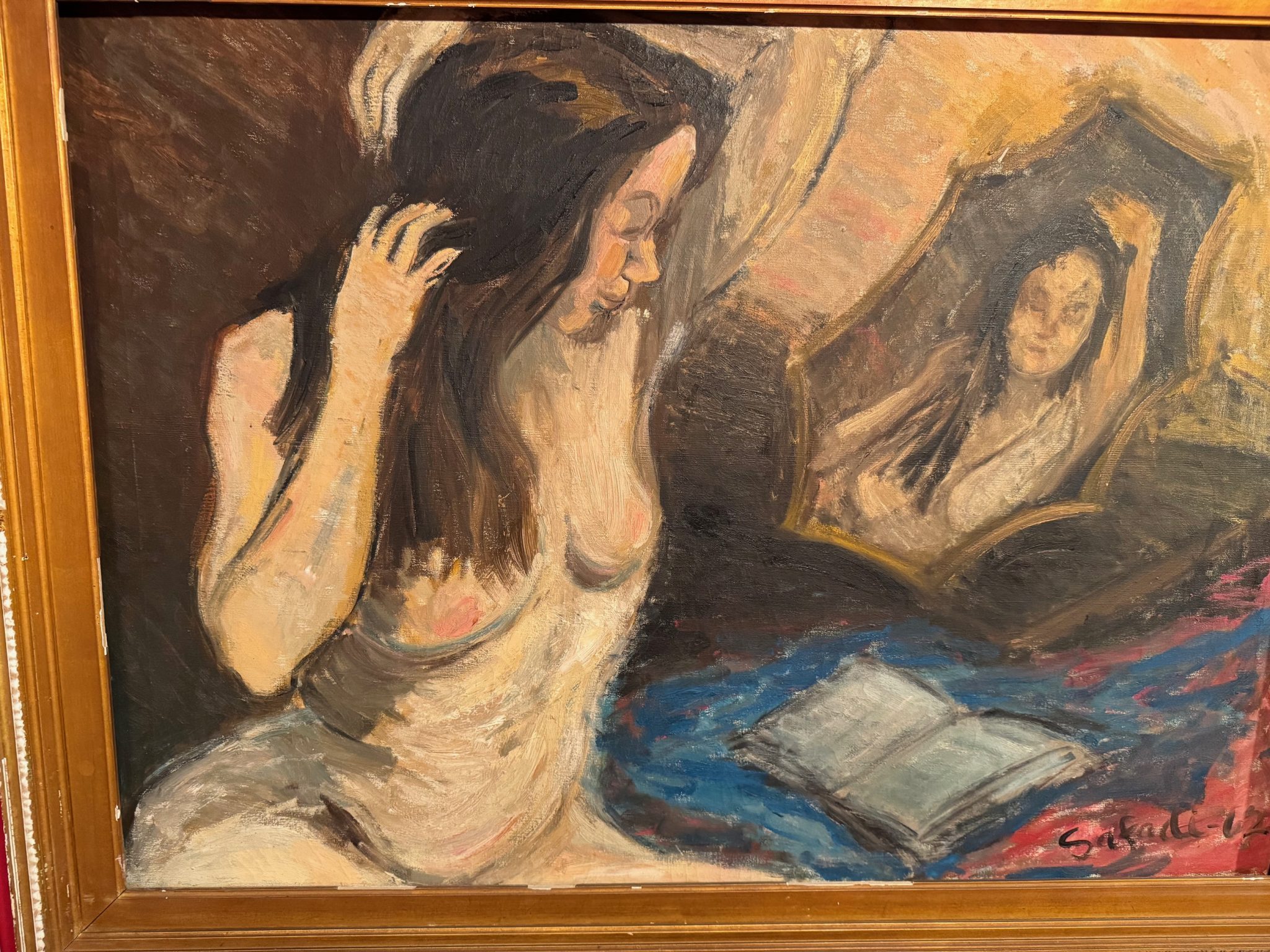

The Museum of Bad Art is highly entertaining for about half an hour – there obviously isn’t that much bad art out there – and then you can move on to the Museum of Good Art, which gives a window into life in Canada before central heating.

There were several paintings called The Ice Harvest.

They all show men cutting huge blocks of ice and using horses to haul them away. But there was no explanation as to why they were doing this and what they wanted all this ice for. In a country where the winter temperature can drop to -50 C, what would you do with a massive chunk of ice? If you wanted a nice cold gin and tonic, you’d surely have enough ice in your own garden to give yourself brain freeze.

Another painting that took my fancy was The Woman from the Flathead Tribe by Paul Kane. The woman’s profile shows the flattening that resulted from pressure on the infant’s head caused by their wooden cradle.

There were lots of other paintings of First Nation tribes without flat heads, and so I wondered whether these people were totally isolated and had never come across other tribes. Or if they had come across them, had they ever considered not squashing their babies’ heads as a future lifestyle choice?

So many questions and so few answers. Quebec is a city that demands a second visit.